The Q&S Q&A: Journalist Michael Kodas talks wildfires, environmental journalism

Wildfires are ravaging the American West, hurricanes are pounding the South, so there’s never been a more appropriate time for all journalists to produce useful stories about the environment — but those stories don’t all need to be treatises on the impact of climate change. There are good environmental stories out there for high school journalists to share with their communities.

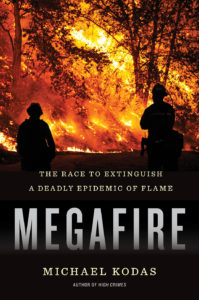

Michael Kodas is the deputy director of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he also teaches journalism classes. His book “Megafire: The Race to Extinguish an Epidemic of Flame” was released in August 2017. He is also the author of “High Crimes: The Fate of Everest in an Age of Greed.”

Quill and Scroll: Tell us about “Megafire.” What is the goal of the book? What can student journalists learn?

Michael Kodas: My goal is to get the general public to recognize their role and their relationship to wildfire and how we’ve contributed to the problem. We kind of have a vision of a huge fire or a really hot fire or a really fast fire, but a very small fire can also be very mega. The Yarnell Hill disaster in Arizona, which killed 19 hotshots, was actually a pretty small fire. So I end up measuring “mega” more by impact than by size or speed or heat generated. Student journalists can think in those terms as well — who is affected and how they’re affected.

Q&S: One of the things you did in preparing to report and write about wildfires was to train as a firefighter. Why did you do that?

MK: Working for the Forest Service gave me access and insights into that job that I wouldn’t have gotten had I just been a journalist showing up. I bonded with this crew, who then taught me how to use the tools and the proper terminology and the various challenges. It helped me tell a different story.

Q&S: What are the dangers inherent in participatory journalism?

MK: You must make sure that your loyalty remains with your reader. Our obligation is to the truth, and our loyalty is to our readers. At the end of my time as a forest firefighter, I got a tip and discovered that we were fighting a wildfire in an area where Dick Cheney had a fishing trip. The commander was saying, “Yeah, the only reason we’re on this fire is that the Vice President has a fishing trip planned in this area.”

I had a number of firefighters corner me very angrily saying, “You can’t report that because they’ll know you are part of our crew and we may not get as good a job the next time.” And you know, obviously I’m concerned. I don’t want to hurt their ability to have a livelihood and make a living fighting wildfires. On the other hand, what was going on was putting other firefighters at risk. So in that case my obligation to tell the truth to my readers and to inform them about how the system works won out.

Q&S: You noted that our first duty is always to our readers, but what else do students need to keep in mind as they’re reporting on communities they’re a part of?

MK: We’re not doing journalism because we want people to like us. And in an academic or high school environment, you’re reporting on people that you might consider your friends or acquaintances. You can’t hold back just because you got that information about somebody you might be friendly with. And that’s a real challenge. So, you know, to kind of be able to step back and say, “Hey, I know you’re my buddy,” but you’re working as a reporter now, so you know you have an obligation to share what you would about people you know just like you would about people you don’t know.

Q&S: What environmental stories can students report?

Kodas: Wildfire is a great example. If you study the scientific literature, one of the areas that’s anticipated to have a huge increase in unwanted fires is actually the Great Plains states, where we don’t really think about wildfire. But we’ve seen a big increase in wildfires in Texas and in Oklahoma and in Kansas. So, just because it’s not happening in the big mountain forest and doesn’t produce those gigantic plains doesn’t mean that it’s not going to be a story for high school students.

Half of the time fires are more beneficial to the landscape than they are detrimental to it. And so you know when we talk about fire on the landscape it doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative story. We can talk about how important fire is to agricultural communities because of its ability to nourish the soil or to help cattle gain more weight because the grass is so much more nutritious after a fire, which is the case in Kansas.

In the bigger picture, the first thing that I think students should do is consider who their audience is. Is it students at your high school? Is it young people about your age but not necessarily just at your high school? Is it the public at large? Is it administrators at your high school with the parents? And think about who you’re writing for and then you can use that to kind of narrow your scope as to issues that you might look at.

For instance, if you’re a high school student and you’re writing for your high school paper, are there environmental hazards in your high school that you might want to look into. Does the football team play on artificial turf, and are there issues with the type of turf that’s used there?

Is there asbestos in your school? Those are all pretty basic environmental stories.

One thing that was incredibly under-reported until the last two years, and now suddenly everybody is doing stories on it, is lead in water supplies. The Flint, Michigan, situation was proved to be not only an environmental toxin story but a very significant environmental justice story. Stories like that are right for high school journalists to look into. If you really want to do something fun and exciting, get a sample of your water and have it tested and see what — lead, arsenic and other elements — are in it and then you can, go to the administration and ask, “Hey why is our water not as good as it could be?”

You can also think in terms of environmental justice stories. Are there students at your high school who are more impacted by environmental situations, say, a chemical plant or a landfill in the neighborhood? Other students may be involved in activist activities to try to change something in their community.

Q&S: Where do students find credible sources to tell environmental stories?

MK: Well, you know finding some experts to interview can be really helpful if you find the right experts who can really explain it to you in simple terminology. I’ve read, you know, by my last count well over 400 scientific papers on wildfire. I don’t necessarily recommend that to anybody, but some of the people who wrote those papers are actually really great communicators. And I realized after having read their paper and then calling them that boy, if I had just called you right off the bat, you would’ve explained it to me with a couple of really great quotes, and I wouldn’t have had to spend so much time in the weeds of all of this scientific jargon.

One thing to recognize in reporting on environmental stories is that you’re going to have a range of sources who are more neutral than others. So you know you may have a scientific expert from a federal laboratory or a university. They can talk to you about asbestos in schools or wildfire or lead in water. And you also have people working for organizations like Greenpeace or the World Wildlife Fund or the Nature Conservancy. People from those organizations aren’t necessarily bad sources but they’re often not what we would call honest brokers. And that’s not to say that they’re liars. It’s to say that they’ve got a dog in the fight and they have a particular point of view that they are promoting.

Q&S: How can students report on climate change in their own school districts, in their own communities?

MK: There are a variety of approaches that would be the same for high school students as they would be for anybody covering another community. For instance, what is the school doing to deal with climate change? Are they promoting carpooling? Are they installing solar panels on their roofs so that they have less of a carbon footprint, maybe re-insulating the school, or doing other things to conserve energy which is definitely a positive thing to do?

Then you can start looking at your student population. What is the sense among the student population? Are there students there who are really active as far as say climate change or another environmental issues? Is there a debate within the school communities that is worth looking into? Do the students’ attitudes match the attitudes at large in the school district, the county, the state?

Another way of looking at it kind of gets back to what I talked to you about before, looking for impacts on the student body. So, do you have students in your school who come from an agricultural family who were being impacted by drought? Do you have students in your school who come from agricultural families who don’t think it’s affecting them?

Q&S: Is there anything else you want to say to several thousand high school journalists and their advisors?

MK: We’ve seen young reporters working at high schools and universities break some really significant stories from the last few years. And with high school journalists they might think, well, environmental reporting, it’s science based and there’s numbers and there’s all this stuff that, you know, I’m just not educated enough yet to understand. I would encourage them not to think that way. You can always find an expert to guide you through the topic with a phone call to a university or to a researcher or to a laboratory. The policymakers and corporate interests who are dealing with environmental issues owe a high school student an answer as much as they owe a reporter from the New York Times an answer. And very often they’re more willing to talk to high school students than a big-time reporter because they may underestimate you, and being underestimated as a reporter is very often to your advantage.

Comments are closed.